Creating a Living Legacy: Jaune Quick-To-See Smith

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith

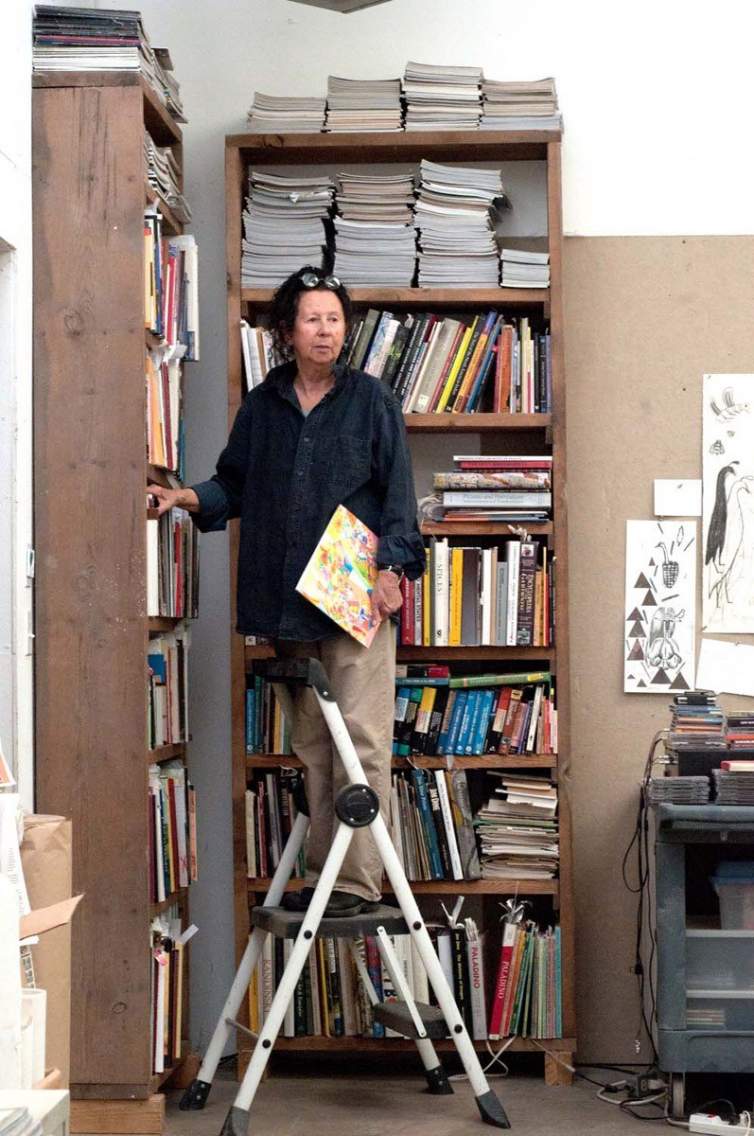

I had an insurmountable problem with a horrendous discombobulated mess in the storage of my artwork. My artwork had accumulated over 40 plus years in the B.C. era (Before Computers.) Prior to the Joan Mitchell Foundation stepping in with their CALL Program, I had eight large folding tables with folders, crates, print editions, drawings, paintings on paper, piled to the ceiling, with piles under the tables. There was manual organization such as boxes of slides, Polaroids, 3 x 5” cards and a couple of file cabinets. But this didn’t help me locate a print or drawing when I needed it for exhibition. It was a hard slog unloading piles to search for the needed print or drawing. My locker storage in town with paintings was in a similar state because I used the “refrigerator technique”; the last thing in pushed everything else to the back, so that I depended on memory to locate paintings or framed works.

Step #1 was choosing a numbering system that would give me fast information–my initials, the media such as a painting, print, drawing or a photograph, the year it was completed and an individual number for that piece. Step #2 was setting up an “unloading dock” to disassemble my years of stockpiling work. Step #3 was for Neal Ambrose-Smith (an artist and also my son, who helped organize the project) to set up a makeshift photo studio and shoot each piece of work, which went right into the computer with its number. Step #4 was sorting the work by year into steel flat files purchased with the Joan Mitchell Foundation grant. A similar process took place at the lockers, where paintings and framed works are stored on temporary steel shelving and racks that we can take apart if we change storage facilities.

The difference between living in bedlam or chaos or waking up in the middle of the night worried about how to meet a deadline for an exhibit versus peace of mind, knowing that you can go right to the location where something is stored. As they say, location, location, location.

The biggest thing I’ve learned is that I don’t need to spend hours searching for something, that there is help out there to create order in your life, and this gives me more time to work in the studio. For older artists, administrative work can consume our time and energy, simply because our working lives were mainly in the B.C. era. Of course, now technology is changing all artists’ lives.

Absolutely, immeasurable, unfathomable, infinite. I have been able to prepare lists of prints with images for a future print retrospective. I was able to accept the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum’s award of Living Artist of Distinction because we could locate the images they requested. There have been several other exhibits since this project began that I might not have been able to do, simply because in the past, I wasn’t able to locate the artwork or the images. This is life changing, career changing. I’m not saying it is easy: it’s fraught with emotion, it’s hard work and causes disruption to an older artist’s routine.

Younger artists who have grown up with the technological age should be documenting every piece of artwork with a number, a digital photo (low and high resolution) and should be using a computer program that allows them to catalog their work. Older artists who can afford to hire another artist or a grad student who is computer savvy, should start the process of numbering, documenting and creating an organized storage system that meets their wishes. Older artists who cannot afford to hire a helper should apply for a grant. Soon the Joan Mitchell Foundation will publish a workbook giving fundamental and helpful advice on documenting an artist’s work.

Yes, every artist, young or not so young, needs a will. A will that allows for change over time and one that gives instructions about where the artwork should go upon the artist’s demise. Artwork is different from cash and real estate.

The aforementioned documenting process of creating an archive (artwork, art collections, writings, books, correspondence, ephemera) will encourage art historians, museum curators and collectors to view an artist as a serious professional. In the end, having this documentation makes it possible for arts professionals to study the work and write about it, thus creating a lasting legacy. Another consideration is that if there is a catastrophe, such as fire, earthquake, tornado or a Katrina, an artist’s work that is stored on a hard drive at a distance from the studio, will live on, even though the artwork itself is destroyed. Finally, something we all should be apprised of, is that in the future more people will see our work, worldwide, in cyberspace than will ever see our work in person.