In the Studio: E Marshall

"The actual physicality of making the line and then making a line next to it fee...

Camille Farrah Lenain is a New Orleans-based photographer and Fall/Winter 2021 Artist-in-Residence at the Joan Mitchell Center. We interviewed her about her work and residency experience in December 2021. The following is an edited transcript of that conversation.

I'm a documentary and portrait photographer. I work in long-form projects, usually I'll have an idea and then it takes me a year to do research, just letting the ideas bubble in my head. Eventually, I’ll pick up the camera and start working on it. I'm also a multidisciplinary artist, working with video, interviews, audio recordings and archives, expanding the options for these different layers of storytelling.

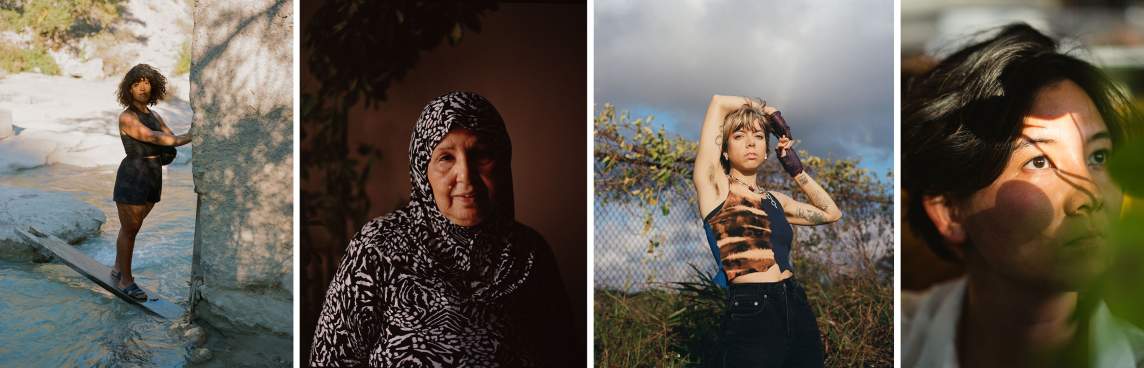

Often, the stories I want to explore are about people and communities who carry plural identities. I’m interested in understanding representation, especially in photography, because sometimes we underestimate the power of photography and how that dictates someone's identity. I tend to question stereotypes or to look at stories that have either been wrongly or not fully documented, not represented in the full spectrum. For me, that’s connected with understanding history a little bit better, understanding memory a little bit better. All of these themes—representation, memory, plural identities—are based on my own experience growing up as a mixed-race child, moving around a lot and kind of wondering where I belong.

I call my work empathetic photography, or empathetic portraiture, because I believe it’s important to try to understand the person you're photographing to the fullest. I’m also questioning a lot of the language around photography. For example, I never call the people I photograph “subjects.” I'm trying to avoid the words “shooting” or “taking.” My approach has been about deconstructing and decolonizing photography—with all those words, with all the massive white and male gaze that it has had. There is a lot of terrible history in photography; people have been exploited on the other side of the lens. So, I’m really aware of that—my vocabulary, my body language, and the relationship with the person portrayed—and I'm trying to figure out ways not to repeat this history.

I’m also really thinking about who takes up the most space in the documentary photography realm. It's changing today slowly, as there are more BIPOC photographers being exhibited, published, recognized. Some of the artists that were hugely inspiring for me are Deana Lawson, Dawoud Bey, and LaToya Ruby Frazier. They are Black photographers portraying the Black American experience in a more slow, meaningful, and nuanced way. And they are challenging why it’s important for them, as Black Americans, to also be the one behind the camera, telling these stories.

When I start a new project, sometimes the focus can be narrow and expand as I go. And sometimes it’s more of a broad idea that focuses over time. I usually photograph people I don't know, so when we meet up, we try to take at least a three-hour window. We speak for an hour or two before I even start making photos. I observe and try to understand potentially how the person wants to be portrayed. That creates the possibility for collaboration, where you can ask a person how they want to be photographed, or you start planning together and you're like, "Oh, you said that you are a really modest person, let's explore this notion together.” Sometimes we end up photographing for only 30 minutes or so because we really got into a deep conversation. Then, maybe a year later, we'll do another session. And six months after that, we'll have a conversation about these photographs. We talk about what we saw in it, what it meant to us now—these little things. It keeps evolving and keeps growing because people's identities change, too.

I have two main projects I'm working on now that really demonstrate my approach. One is a project about LGBTQ+ identity inside Muslim culture in France—people who are practicing Muslim, or people who grew up with some sort of Islamic presence in their family or surroundings. I’m doing this project as an homage to my uncle Farid, who was Algerian and gay. He had diabetes and AIDs, and he passed away in 2013. In this case, I started the project with this narrow focus around him, around my family, but because it was sometimes hard to have these conversations I extended it further to the LGBTQ+ community, including people who question faith and society in France. They constantly challenge stereotypes, and have to interpret their own singular identity, which is hugely misrepresented. This project has honestly been a beautiful journey. I’ve met inspirational people that I count as friends now, and most portrait sessions are transcendental. I leave exhausted but full.

With the other project I’m currently working on, the idea started really broad: I wanted to do something about rural Louisiana women. So around three years ago, I started meeting people, talking to them, honing in on women who work with the land, and then little by little it became about women hunting. Huntresses.

I was interested in the idea of women doing work in what are historically seen as more masculine roles, like farming and hunting, and exploring their relationship with the land. One of my good friends is a huntress, so when I was able to experience that with her, I became fascinated. I have a group of friends in rural Louisiana, so I'll go sleep there in a tent, and when I woke up one morning, there was a dead hog on the boardwalk by the pond, and then an hour later I'm eating it for breakfast. My friend, she just picks up a huge snapping turtle and then puts it in her truck, and then we drive back to her place, and she's like, "I'm going to make some soup later. It's going to be really good."

I grew up in cities, so I was just really excited and curious as soon as I started thinking about hunting, and doing more reading. The mythology aspect of it really fascinated me too, because in mythology, the goddesses embodying the hunt are feminine. So then I question, why do we always think of men hunting? I started digging and then I realized when I started documenting all these women hunting, they have to carry a lot. They have to carry different roles and that is their strength. What's strong about them is not that they kill animals, it's that they are nurturers, they are killers, they are mothers, they are the one person in the group that is different if they go with a bunch of men. So for me, it's not, "Wow, you're strong because you have a gun or you have a bow." It's because you just walk gracefully with all of those identities and I'm just fascinated with that in general.

With the huntresses, when I think of the audience for this work, I want to be thoughtful over how those images are brought out in the world. Beyond the photographs, I also want to have audio recordings that tell the story from their voices, so viewers have the option to hear from the women directly. I want to invite the audience to be in a space with other people that they're not used to being with in both urban and rural areas. I don’t want it to just be all the same audience that goes to the museum. I want to make sure there is multiple outreach because I think that's a big problem today, people staying in their communities, lacking context for other’s experiences.

One thing that really made me want to become a photographer, I think, was visiting New Orleans, which I first did about ten years ago, and then I found ways to move back here. I didn't work as a photographer at first, I taught French in schools, I worked in restaurants, I played trumpet, I did a lot of different things before slowly figuring out how to work as a photographer. When I first visited, I spent two and half months photographing everyday. But then, when I moved here, I stopped documenting in the city because it was overwhelming seeing how many people have photographed this place. It’s been over represented through the lens of visitors, outsiders, and new transplants. I wanted to understand it more deeply, understand the history and the culture. So it’s interesting to look back on the work I did here almost 10 years ago. Now, in my ninth year here in New Orleans, I'm slowly starting to photograph it again.

Learn more about Camille Lenain's work at camillelenain.com, and follow her on Instagram: @camille.lenain.