In the Studio: Samira Abbassy

“My attempt in depicting the human form is almost like a psychic x-ray, so the n...

Chiffon Thomas is an artist based in Inglewood, CA, and a 2022 Joan Mitchell Fellow. We interviewed him about his work and creative practice in May 2023. The following is an edited transcript of that conversation.

The basis of my practice is that I'm trying to touch what it means to be alive, what it is that flows through everything that we do. It makes me reframe the world around me to understand it better and to touch it, to feel it, to taste life.

I'm really interested in relational aesthetics and the body in relation to objects. I see a symbiotic relationship between biology and industrial structures and how they relate to each other, in that a lot of the things that we make functional in the world are by copying nature. In my work, I play around with this duality—a body becoming a structure or the structure becoming a body—while also maintaining the tenderness and the fragility of the body, which may seem structurally sound but still needs care.

It's very stimulating for me to learn about the history of the materials that I use, like its function or purpose or its origin, why it even came into being in a process that we continue to practice and use. I’m drawn to things that I feel are elegant and beautiful, whether that is from the actual design and adornment of an object, or through weathering and patina. Nature's palette is super beautiful to me.

I also gravitate to things that are old and have their own timeline, their own life. I'll never know the full history of an object, but I know it may predate my time here. I like the idea that it carried out a lifetime undisturbed by me possessing it or not. And that's interesting to me because I'm curious about what a witness is doing with it, what care was given to it, or neglect or vice versa. What were its roles? What was its purpose?

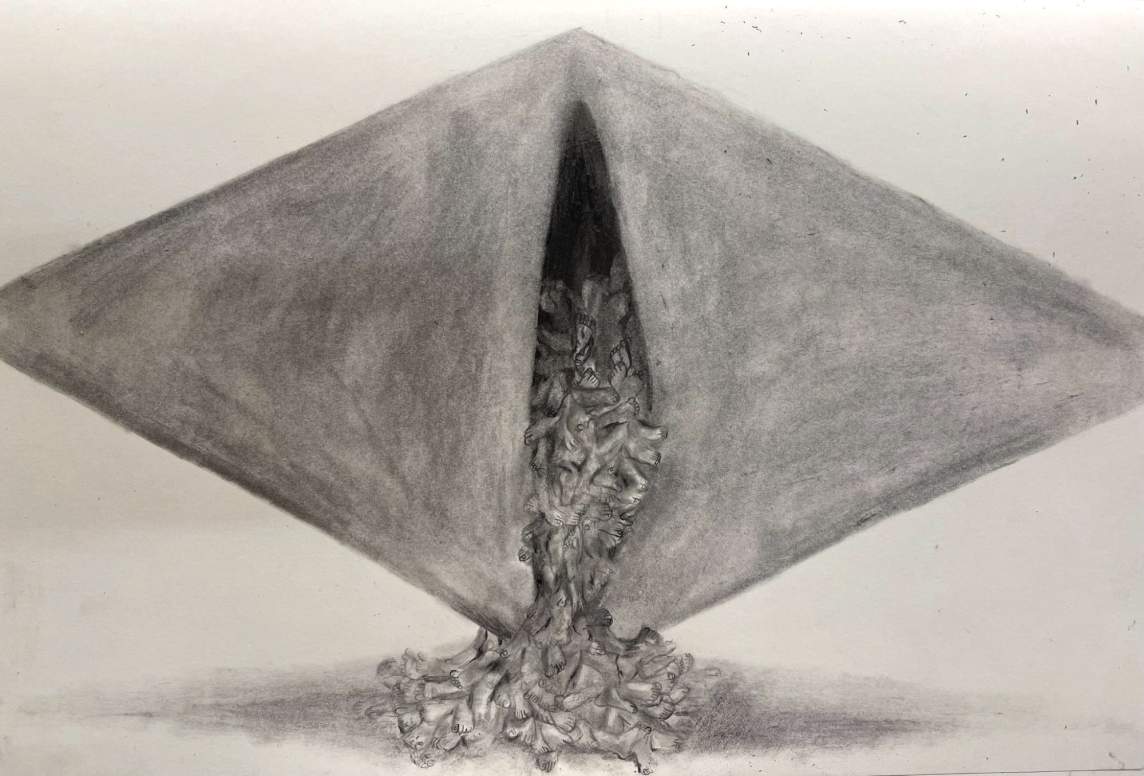

I use a lot of columns and other architectural elements in my work. Along with things that feel like a part of this reality, I like things that are a little bit adjacent to reality or feel otherworldly. So right now, I'm working with geodesic domes and obelisks and pyramids and things that connect the world that we know to the sky or the unknown or a celestial force.

I'm really interested in monuments and in the body being an armature of a monument. There are these symbolic approaches that our species has developed to show this act of ascension or connection to the heavens and the earth. Why do we commemorate the dead or the deceased? Why is that important to us? It’s something that's genetic. It's a part of the evolution of our species. It is something that we do traditionally with the non-living body and there is this respect that is upheld for a life that happened and is no longer here. But sometimes the living body is not regarded in the same way.

As I said, I'm interested in biomimicry and how we imitate patterns that are from the natural world. I listened to a podcast recently with Adrienne Maree Brown, who was saying it's not a coincidence that if we look at our fingerprints and we look up to the sky and into the stars and galaxies, a lot of those patterns are repetitive on a macro and micro level. And if you just stay within the pattern of the natural world, things flow fluidly. But the disturbance of that, through greed and corruption, creates disjointedness and dysregulation. Now look at the state of the world, with climate change and politics and people being mismanaged and enacting hierarchies over another person…

And then I look at the ancient civilizations and think, How did they build these monumental structures with so little? How did they think about these structures? What is the purpose of these forms and what were they trying to emulate? They looked to the natural world, because we are natural. And with that, you have no limitations.

Right now, I’m making a series of geodesic domes for a show at the Aldrich Museum, in Ridgefield, CT, that's opening on September 14th. The show is called The Cavernous. I've been working really hard on this show, making some of the smaller domes here in my studio, and there are other large-scale domes that I have help to produce. The geodesic dome is doing a few things. It’s structurally designed well, it feels monumental, and then you have this body in submission to this structure. It's tethered to it and this is the only form it can take because of the weight of that structure. There’s something in that gesture, and the dichotomy between the two things... You got this structural thing that's also hindering the body. They are confined, but operating within the structure that is overtaking them.

It’s similar in a way to these angel pieces that I make with a figure and columns that feel like they have wings—like they are a winged person. I have one that I showed in 2021 where the wings are so heavy that they crush the person into the wall. You think that this thing is supposed to be able to ascend in the air, but the columns are too heavy and oppressive that they create this disturbance. It’s like, you just can't live out your full potential.

Alongside the show that’s coming up at the Aldrich, I'm having a second solo show at Kohn Gallery in LA, so I’m making work for that gallery show as well. I just started making these architectural structures with this skin-like pattern that's emulating stained glass. The architecture is literally embodying, it's wearing a person, as opposed to it dictating the position of that person's life or using it. I'm trying to connect these ideas—about religion, or I don't know, just our social engagement.

There’s this connection that I see between the body and the way that we structure our societies to control and to manipulate. But you still are trying to maintain some kind of life within it. You still have to operate under the confines of these systems. What is the cause? What is the result of that? And genetically, how do you pass that down into intergenerational trauma? And then how do you still get reminded of the history of that?

These objects, they're codifiers of that. The geodesic dome is not made from material that has a colonial reference, like the columns, but they reference sustainability or affordable housing or the idea of everybody having shelter. But in the same vein, they are also mobilizing this figure. It's an efficient space. It's a vast space. But through mismanagement, it can always be a prison. It can always be on the cusp or the precipice of turning the intention. And that is what all of these objects are trying to do. The stained glass with the skin is just a hairline away from being distorted intention. It could be for good. These stained glass things light up, they can illuminate and the skin can also be illuminated and translucent. It can do positive things, but it could also be very negative.

My work is evolving into these more monumental things. The Joan Mitchell Fellowship has been so great because I’ve been able to envision bigger projects like the big domes. I want to make public art pieces. I think that that is where I'm headed. I’ve got a huge book full of monumental drawings that I've been creating. I don't use Photoshop, so I have to rely on drawing to work out my designs and figures. I refer to my drawings so much that they get damaged. Some of them are just destroyed by the end of a project. I need to recreate them. I got this huge, expensive leather-bound sketchbook to try to not feel the need to cut the drawings out of the book.

In this drawing, the obelisk is being created as a single pair of feet that grow into a monument. I'm really into feet right now. I feel like these things should be out in the park, in space, and I've just been making different angles of them. I want to have a full show sometime just of my drawings, because they're very detailed. With my drawings, I can do things that I cannot do in the real world.

Interview and editing by Jenny Gill. Learn more about Chiffon Thomas’s work here.