In the Studio: Samira Abbassy

“My attempt in depicting the human form is almost like a psychic x-ray, so the n...

Drew Kahuʻāina Broderick is an artist, curator, and educator from Mōkapu, Koʻolaupoko, Oʻahu, and a 2022 Joan Mitchell Fellow. We interviewed him about his work and creative practice in June 2023. The following is an edited transcript of that conversation.

Mau ke aloha, no Hawaiʻi. Love always, for Hawaiʻi. This is what motivates me at the moment. I care about Hawaiʻi, I care about its peoples, I care about our stories. Especially stories of art and exhibition-making that have been passed on within Native and local communities but remain to be acknowledged meaningfully within many museums and educational institutions.

Making things no longer interests me in the way that it once did. Over the past few years, I have become more and more committed to the stewardship of relationships. A lot of my energy goes into serving the creative practices of family and friends. This sounds, looks, and feels differently on different days—redistributing grant funds or helping to submit grant applications; assisting with the production, transportation, and/or installation of artworks; organizing exhibitions, writing catalog essays, moderating panel discussions, documenting events, and archiving materials; cooking and cleaning; whatever is required, this is what it means to be in community.

As a specific example, from January to August of this year, I’ve been collaborating on an intergenerational exhibition of Kānaka ʻŌiwi, Native Hawaiian, contemporary art presented within six venues on four campuses of the University of Hawaiʻi System and the East-West Center on Oʻahu. ʻAi Pōhaku, Stone Eaters brought together over 120 works of art by more than 40 artists and activists created over the last five decades, from 1976 to present. The first large-scale exhibition of Kānaka ʻŌiwi contemporary art within the University of Hawaiʻi System since its founding over a 100 years ago, ʻAi Pōhaku, Stone Eaters functions as an act of affirmation and resistance. While providing much needed opportunities to celebrate our creative expressions, it calls for increased support by institutions of higher education.

No matter what I’m engaged in, it’s important to me not to be bound by any particular discipline, material, or way of working. The only aspect that remains consistent across the various projects I’m a part of is that they always begin with conversation and, in that sense, often become something different than what anyone thought they were going to be. Sitting down with folks and talking story is about letting go of expectations around final forms, methods of production, and assumed roles. It’s about adjusting in real time as a process unfolds.

![“longstanding, ongoing: a project in parts” is installed in a gallery room corner: at the center is a road-side inflatable tube man with American flag markings, folded in half at its midway point where it hits the low ceiling, so its smiling face is upside down and its fringed head and hand touch the ground. On the white walls are 2 rows of small framed photographs in a group of 5 and a group of 3, and below them read [wind blowing] and [waves crashing]. The plywood floor is marked with fluorescent orange and white spray paint, and two traffic cones (one toppled) are at each side of the inflatable.](https://www.joanmitchellfoundation.org/uploads/journal/_1144xAUTO_crop_center-center_65_none/5-ITS-Broderick-05_longstandingongoing_2021.jpg)

Because Hawaiʻi is located over 2000 miles from the nearest continental land mass, at an intersection of the so-called East and West, there’s all these colliding forces at play, entwined histories in the mix. When we unravel dominant narratives, those that have been imposed from a distance and regulated from within, we come to know lesser known stories that have been systematically neglected, covered over, erased, but also remembered and reconstructed. And that's part of why I believe in bringing a genealogically and geographically informed approach, one that is both chosen and given, to the work that I do. If we don't understand how we've arrived at this current version of present day Hawaiʻi, then we certainly won’t be able to reimagine and actualize more just futures beyond those that are already coming.

Many of the folks I collaborate with are also interested in the complex and often contradictory archipelagic realities of Moananui, and are coming at them from different ethnic positions and cultural perspectives. And so together, we're able to engage collectively in ways that we could never on our own as individuals. This is why solidarity, why Native/non-Native collaboration, why aligning my work with the work of other islanders, matters to me. There is a different appreciation, approach, and worldview that comes from day-to-day island life and ocean living.

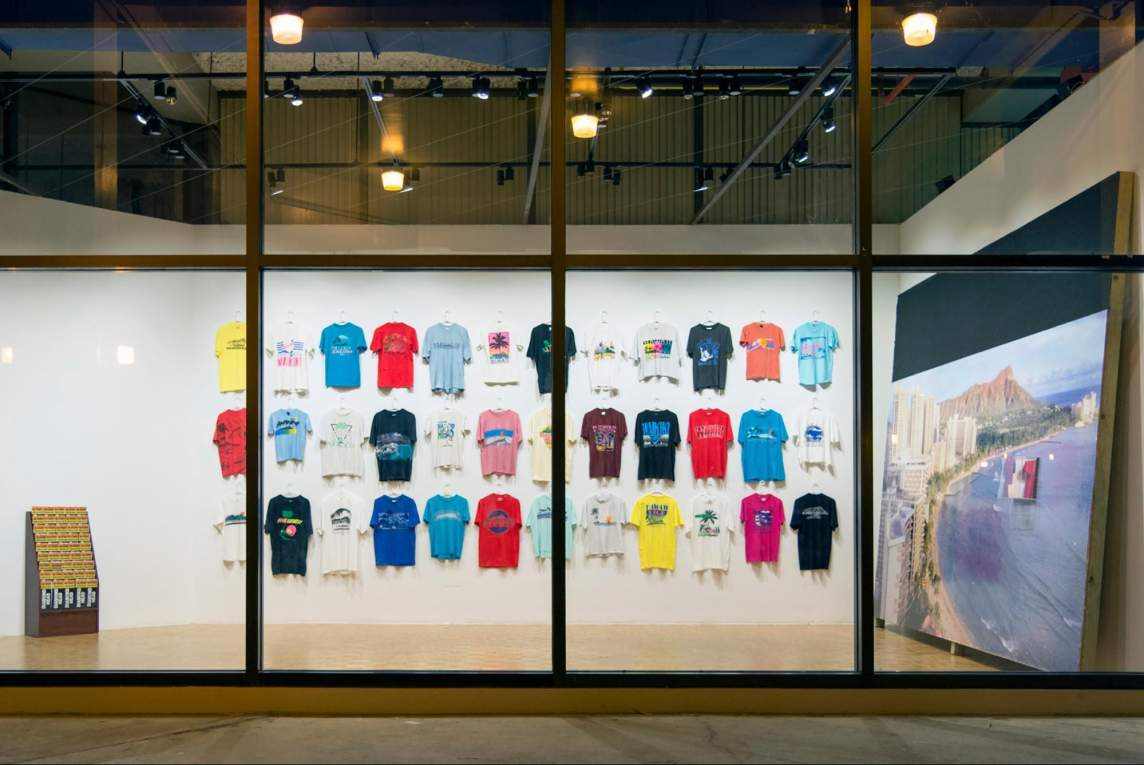

Legacies of colonialism and the current impacts of ‘militourism’ here in Hawaiʻi and throughout Moananui have been a focus of my work for some time now. “Militourism,” as poet, scholar, and educator Teresia Teaiwa defined it, “is a phenomenon by which military or paramilitary force ensures the smooth running of a tourist industry, and that same tourist industry masks the military force behind it.” “Although military forces and tourism provide employment and social mobility for many Islanders,” Teaiwa elaborates further, “they also drain or pollute natural resources, endanger sacred sites, and introduce unhealthy ‘convenience’ goods.” In the early 2010s I started thinking through this dynamic alongside independent curator Gan K. Uyeda and in 2017 we collaborated on a small project, Diamond Head, that took the form of an exhibition and accompanying publication.

Diamond Head or Lēʻahi as it’s known to us is a volcanic tuff cone that rises roughly 760 feet above sea level, with views of Kohelepelepe in the east and Kaʻala in the west. It is a result of a single energetic explosion that occurred hundreds of thousands of years ago. In 1906 this storied place was forged into Fort Ruger, the earliest U.S. Army coastal defense fortification in Hawaiʻi and an integral part of a massive operational hub for American power projection in the Pacific. The U.S. military occupied the crater into the 1950s. Diamond Head was designated a State Monument in 1962 and a National Natural Landmark in 1968.

Across the second half of the 20th century, Lēʻahi was transformed again, this time not into a military installation but instead, a mass-produced symbol of ‘Paradise,’ reproduced without permission on postcards, tshirts, and backdrops of a booming militourism industry that now hosts millions of visitors a year. Preconceived fantasies aside, Hawaiʻi is not a vacancy, a backlot, or a wasteland. Hawaiʻi has its own stories, stories that continuously challenge the imposed aesthetics of military fatigues, tropical print shirts, and beach towels. Securing a place of leisure is insignificant in comparison to ensuring the continued existence of a place itself. How do we, those who have the privilege of living in this place, relate to it in a more caring way?

By reconnecting to the particularities of place, my creative practice led me back to family—specifically to my mom, her sisters, my aunties, and their mother, my maternal grandmother. They dedicated their lives to supporting Kānaka ʻŌiwi artists and artists of Hawaiʻi. It's a lot easier for folks to rally behind Indigenous artists now, but my family has been doing that for generations, not because it's on trend or because it's ‘good business,’ but because it’s who we actually are and what we actually believe in. We understand that supporting Kānaka ʻŌiwi art and art communities is vital to what makes Hawaiʻi, Hawaiʻi.

In my teens and early twenties I tried to distance myself from family, as we sometimes do when we're young. But when I finally got over myself I realized that what I really wanted to do was collaborate closely with family, to contribute to the efforts in arts, education, and organizing that they had been leading and participating in for decades. I have so much to learn from them, from their stories and experiences. So that’s where I'm at right now and one of the main reasons I moved home after graduating from Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College.

In 2019, I accepted a position at Kapiʻolani Community College caring for Koa Gallery and teaching in the Arts & Humanities Department. In parallel, from 2020 to 2022, I curated the Hawaiʻi Triennial: Pacific Century – E Hoʻomau no Moananuiākea with Miwako Tezuka and Melissa Chiu. As part of the large-scale periodic exhibition I had an opportunity to collaborate closely with artists who are also family and friends, including ʻAi Pōhaku Press, an imprint established in 1993 by my mother, Maile Meyer, and her lifelong friend, book designer Barbara Pope.

More recently my mom and I had a chance to participate together in Singapore Biennale 2022. We organized a project called KĪPUKA [for “Natasha”] at Sentosa Cove, an island resort residential zone. Presented within an altered shipping container resembling a makeshift Visitor Center, KĪPUKA brought together offerings from an intergenerational group of family, friends, and frequent collaborators—ʻĪmaikalani Kalāhele, Wayne Kaumualii Westlake, Protect Kahoʻolawe ʻOhana, ʻElepaio Press, Nā Maka o ka ʻĀina, Tutuví, ʻAi Pōhaku Press, Native Books, Nā Mea Hawaiʻi, Lawrence Seward, Bradley Capello, KEANAHALA, and kekahi wahi, among others. And the experience really helped reinforce the importance of relationality, of going against “the artist as individual.” Through KĪPUKA we were able to share the collective efforts of many.

Related to sharing stories and collaborating with loved ones, my partner Sancia Miala Shiba Nash and I recently started working on an open-ended series of no-budget artist videos. The first film, Hoʻoulu Hou, was made with folks from Hoʻoulu ʻĀina, a place of refuge in the back of Kalihi valley dedicated to propagating connections between the health of the land and the health of the people. Hoʻoulu Hou honors the life and legacy of musician, poet, artist, and activist ʻĪmaikalani Kalāhele who has stood as a pillar within various communities for going on half a century. Despite being one of the most revered Kānaka ʻŌiwi contemporary artists alive today, Uncle ʻĪmai has still not received substantial institutional support through a major commission, dedicated publication, or solo exhibition. It’s our hope that these artist videos will help to accelerate positive change and bring attention to artists’ practices while they are still with us.

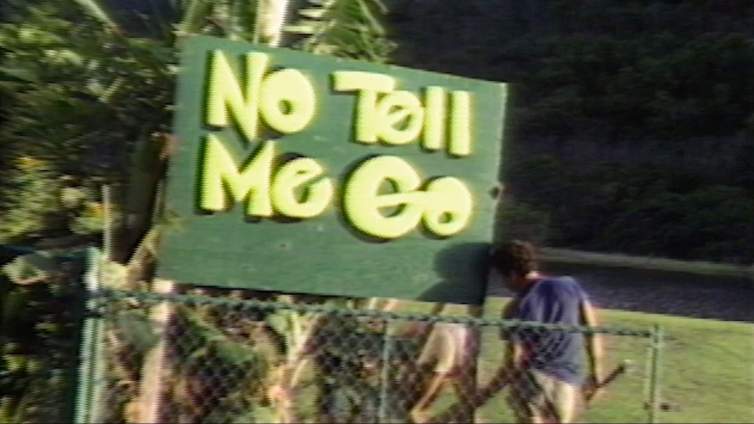

Conscious of the harsh realities that many face in Hawaiʻi, Sancia and I started a grassroots film initiative in 2020 called kekahi wahi, to document stories of transformation. In addition to making artist videos and short experimental films, we also program a community screening series, i nā kiʻi ma mua, nā kiʻi ma hope, featuring moving image works that are of, about, and/or related to Hawaiʻi. The title of the series expands on the well known and oft quoted ‘ōlelo no‘eau, poetical saying, “I ka wā ma mua, ka wā ma hope,” to acknowledge the ways in which filmmakers and artists of today are guided simultaneously by their pasts and futures. Shifting the focus from ka wā— epoch, era, time, space—to nā ki‘i—images, likenesses, idols, petroglyphs—encourages unexpected connections across media formats, practices, movements, and generations.

Interview and editing by Jenny Gill. Learn more about Drew Kahuʻāina Broderick’s work on his website and kekahi wahi’s Vimeo.