In the Studio: Christian Việt Đinh

“My nail salon series is meant to celebrate the success of the Vietnamese nail s...

Henry Payer, Jr. is a Ho Chunk artist who works primarily with collage and mixed media. Payer, who is currently based in Sioux City, IA, is a 2022 Joan Mitchell Fellow. We interviewed him about his work in March 2023. The following is an edited transcript of that conversation.

My work generally has to do with the culture that I come from, and my background as a Ho Chunk, the Indigenous people of Wisconsin. My people were relocated multiple times in the 1800s throughout the Midwest before ending up in Nebraska. So I'm from the Nebraska Ho Chunk, federally recognized as the Winnebago tribe in Nebraska. A lot of my work stems from that history and that area, as well as trying to reestablish the visual continuum of our culture.

I was initially trained as an acrylic painter. After going to grad school, I worked primarily with mixed media—a lot of collage, utilizing found objects, site specific material, historic documents, postcards, and just whatever I could find that could make a mark or that I can manipulate in terms of color or activating the history of a piece.

In 2018, I was an Elizabeth Rubendall Artist-in-Residence at Great Plains Art Museum in Lincoln, Nebraska, and I think of that as the point in my art making practice where I recognized that some ideas require different techniques and knowing when to use them. I was using mixed media, image transfers, found objects, and also trying to make newer things, working with different mediums. That led me to reconnect to working with ledger paper, which has its own art historical relevance within Native American art history, as it represents one of the times that we appropriated materials that weren't our own.

Ledger art was originated by prisoners of war. In the 1870s, various tribes were loaded by train in the south and sent to Fort Marion in Florida. While they were imprisoned there, the guards and surrounding people gave them ledger books and accounting books. And from there, they reflected on their traditional pictographic arts, which was done on animal hides and rocks and birch bark. So it kind of became a transculturation of those new materials—ledger books and ledger paper and colored pencils—and they recorded their former lives, courting scenes, ceremonies, and their war honors. The story is they were allowed to sell these drawings to tourists who came to view the prisoners of war in Florida.

From that moment, when they took the ledger papers and put them on the wall, that's my interpretation of when contemporary native art started, in terms of accessing the materials and things that were given to us beyond our traditional lifestyle and cultural or visual history. Ledger drawing was also happening in the 1860s amongst different Great Plains tribes, as accounting books were taken from dead soldiers or they were commissioned between Army soldiers and Indian scouts, but this account is used as a specific example in Native Art history.

Ledger art continues to be a very vibrant practice today. I use it for its historical relevance, and I try to differentiate how I use ledger paper from artists who are still using that traditional style. For my work, I’m drawing on all my art history and social background. I try to utilize ledger paper in the same manner that the Dadaists and Futurists utilized their paper, like collage and exploring how you can manipulate space and depth. And I value the art over the paper that we're placing value on, and the artwork that's on top of it, in an effort to push my art forward. There's all these different questions that just by accessing that paper, I'm able to tap into—that is, if people are aware of art historical movements, contemporary native art, and traditional native art.

The past few years, since 2019, has kind of been an incubation period of researching and seeing different things in galleries. And so now, I’m at a point where I’m thinking about how I utilize all these different things, and I’m trying to rework acrylic painting back into my practice. So currently I'm doing these hard edge paintings that look like collage because the hard edges are similar to the end result of having something cut out and then placing it on something. I’m combining that as a painting style with collaged elements. And I’m getting back into that identity of who we are as Ho Chunk people, and having to identify as Winnebago and all the things that just saying “Winnebago” brings to mind.

The word Winnebago is a xenonym from an Algonquin word, "winnepiko," which translates to "people of the foul smelling water." In the summer, due to heat and humidity, the lakes in the region can become algae rich and have a particular smell. At the time of contact with the French at Green Bay in 1634, our Algonquin speaking Menominee neighbors gave the Jesuits this information, pointing out our living location throughout Lake Winnebago. The French then corrupted this word, translating it to “the foul smelling people" and giving it negative connotations, or describing us in French as “puants.”

As a people, we call ourselves Ho Chunk, which means the people of the original voice. Due to our relations with various flags—British, French, and American—we have treaty negotiations that state our identity as such, and so our relationship under these flags is defined by these names and identities. This is another reason why self-identifying as Ho Chunk is so important to telling our story.

I'm trying to bring all these things together in my work. Some of my works are self-portraits. Some of them are representative of that pictorial narrative of being relocated into Iowa, to Nebraska, to Minnesota, South Dakota—all these different places that we were relocated to. The power of place is always a thing that I'm always interested in, and our brief time that we were there, and what we have left of that within our oral history.

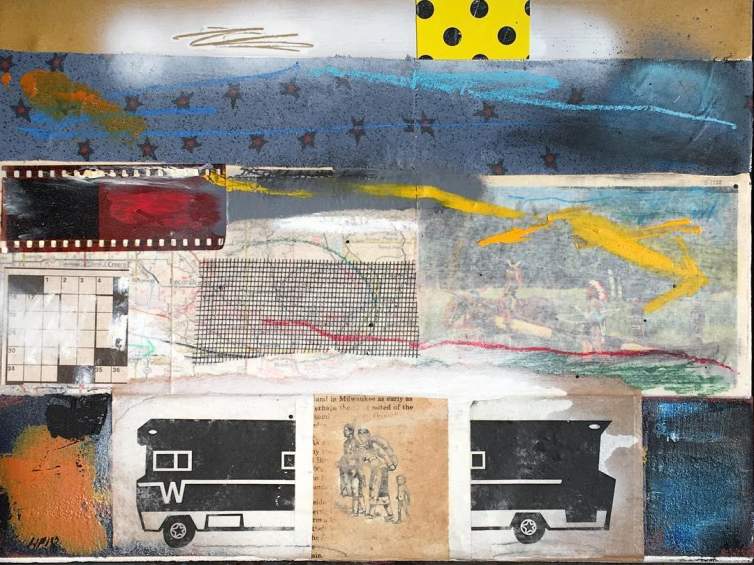

I utilize the Winnebago Chieftain RV a lot in my drawings, collages, and photography. One collage painting from 2022 is based on a stereograph of two Ho Chunk women on their horses in front of a traditional housing structure: the longhouse. I reimagined the longhouse as the direct inspiration which the Winnebago motorhome is based from. As the Ho Chunk were removed, they walked back and forth from Wisconsin to Nebraska and were known at the time as the "wandering Winnebago."

There's a series that I do where I bring a small Winnebago toy with me, place it at different locations, and shoot it with my camera from the ground up. Those are self-portraits at various locations, depending on if we had been relocated there or if I'm just visiting somewhere like Toronto or Quebec. It kind of stands in for a selfie.

I also utilize ledger paper and the Winnebago in collage works. In a lot of these works, the Winnebago is shown in the side view, and that kind of represents moving to east or west. I’m also currently working on Winnebago collages that are front views, and I feel like those are more self-portraits of my travels and incorporate my own history.

I always try to shy away from the idea of this umbrella of “native art,” because we each have our distinct aesthetics. And I try to ground my work in the development of artworks that are based on Ho Chunk aesthetics, as opposed to being a diversion from that. So I do a lot of research into that visual culture, and where that's found is in boxes and storage of museums. I have to go to archives that have our cultural items and objects in them. These are also unnamed Ho Chunk artists who have created their artwork using raw materials or processed deer hides to make moccasins. So there's these different things that I try to stay rooted in.

Visually, I try to represent that in the most accurate way that I can. I understand that having that culture survive is more important than contributing to the "art world," wherever that may be. I always try to ground myself within the values of what defines Ho Chunk art, and there’s a contemporary aspect because I am a modern day, living, breathing, indigenous man.

There’s a performative aspect to how people look at art. I realize nowadays people want the instant transfusion of an image, as opposed to spending time with the artwork. I try to pack my work with historical references so that people can spend time questioning our own motives and presumptions, because we are taught a lot of things. So when I see people come back to the artwork, that's what I hope for, for it to have an underlying effect on them. They might want to know more about whatever it is that's engaged them.

Ultimately, I’m trying to get people to question and learn more about not only their cultural perspective, but about history. This is not just my history that I'm talking about. It's American history. It's regional history. It's state history. It's local history. Indigenous history. I know it can be kind of daunting, but I always try to get people to ask questions, as well as to educate themselves.

I've got a solo show opening in Brookings, South Dakota. It’s one of the first solos since the pandemic. I've got two more solo shows that are in the fall, so I've got my summer booked up, creating more work. I'm thankful for that and the opportunities to be showing. It's good that the Ho Chunk narrative will be out there. I'm thankful that more people are open to learning about not only myself as an artist, but my people and my culture, which is where my work's foundation lies.

Interview and editing by Jenny Gill. Follow Henry Payer, Jr’s work on Instagram.