In the Studio: Mankh

“What I feel like I'm saying with my work is that we all come from the same sour...

Mala Iqbal is a Brooklyn-based artist and a 2023 Joan Mitchell Fellow. We interviewed her about her work and creative practice in February 2024. The following is an edited transcript of that conversation.

I primarily make drawings and paintings. They're typically oil paintings, although for many years I worked with acrylic. I have a very robust sketchbook practice, which is a kind of engine for my brain and eyes and hands. I also do a lot of collaborative work.

I’m interested in narrative and stories. I've always been an avid reader of literature and fiction—books with plot and characters. For me, stories are a way of understanding the world around me—understanding history better, understanding other people, other cultures. I think painting does that, too, in a different sort of way. My paintings are generally sort of ambiguous stories. They're not very spelled out narratives. You can look at them and different things could be suggested to different people. And I like that.

Watching people and looking deeply is something that I feel like I’ve done all my life. I think that partly comes from my personal background and how I grew up. I had two parents from very different cultures. There were multiple languages being spoken, and not everyone understood everyone's language. I was often helping my mother, who was German, to understand what my aunts and uncles were talking about when they slipped into Punjabi, or when my grandmother was trying to tell a story to me in a mixture of English and Urdu. I was always filling in the blanks.

Growing up in New York City, it’s second nature to be watchful, keeping your antenna out and judging the feeling of a crowd or what’s happening on the far end of the subway platform. Generally, even if you're reading a magazine, you have a bit of awareness of what's going on around you. Also, as a kid who was pretty androgynous, in school I was having to figure out who was going to be my friend and who was going to be mean.

I've been drawing ever since I was a little kid, but it’s something that I started doing more seriously in 2009, after I'd seen a show of Bonnard's work at the Met. Aside from absolutely loving his paintings, and the color and the touch in them, the really nice thing about this show was that they had a few of his daybooks. Every day he would write down what the weather was like and he would make a little pencil drawing. They had a swipeable iPad where you could scroll through many more of them.

Bonnard’s daybooks reminded me of the value of having even just a small daily thing to do, because now, as a working adult, I always felt like I was having to wring studio time from a stone. For a while I was trying to go to the studio at six in the morning before work because I tend to be more of a morning person. But that was pretty exhausting!

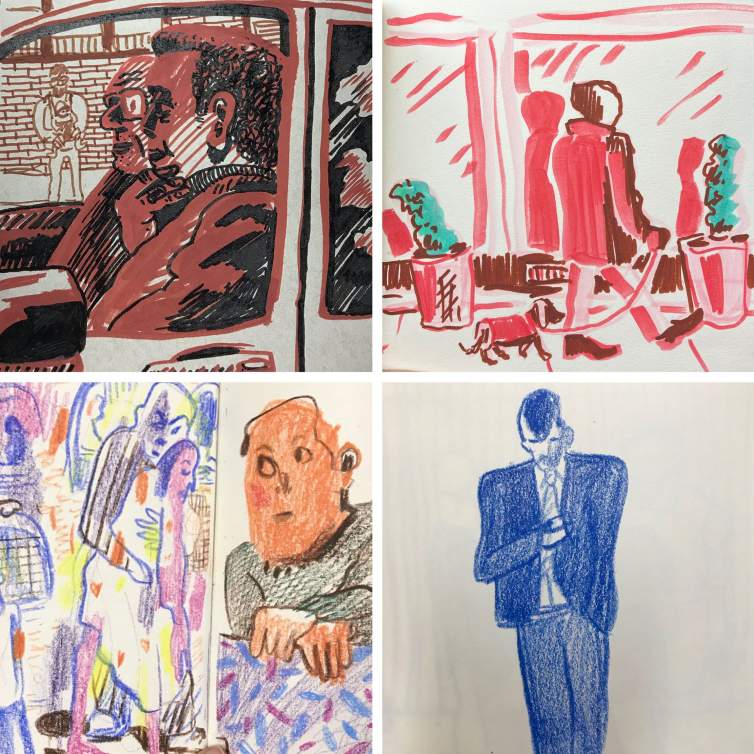

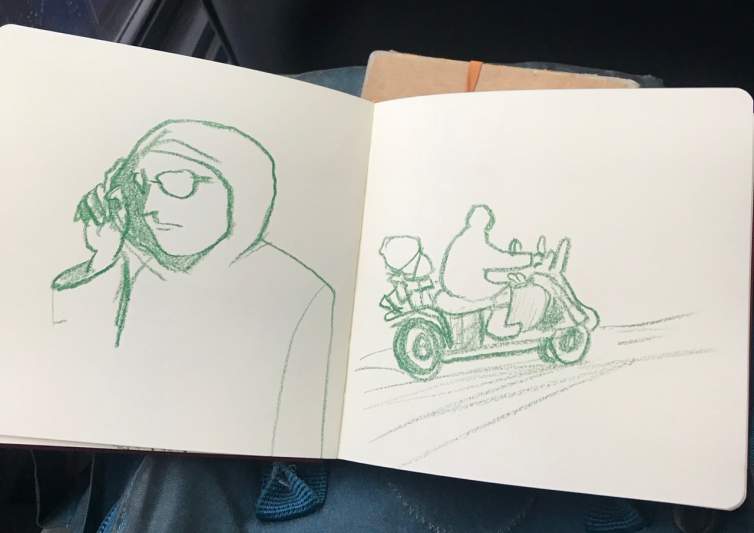

With the Bonnard show in mind, I started drawing on my daily commute. At the time, I had started doing paintings of people within the landscape, so I was still doing that even though I was on the subway or the bus. Then I realized there are thousands of figure models just sitting all around me and all of these interesting faces. New York City is like a smorgasbord of diverse faces and bodies in every sense—age, race, ethnicity, size, everything.

So I started drawing people on the way to work, on the subway and from the bus. They are often quick figural gesture drawings—like in 10 seconds, you look at someone and the bus is moving and they're moving and then they're already gone. It’s like the classic thing you do in art school. You're kind of putting it down very quickly, just capturing the general shape or feel of the person.

I always have at least one, sometimes two sketchbooks of different kinds in my bag. I started trying out different materials—a brush pen, pencil, markers, crayons. It was really interesting to see how changing the size of the sketchbook, the type of paper, the type of material that I was using also changed the drawings very much.

I always put the date in the inside cover, noting when I start and when I finish the sketchbook. You can see the seasons changing based on what people are wearing, but for me also, there are particular life moments that I recognize there. So it's also become diaristic in a way.

There's always been a dialogue between my drawings and my paintings, but they're separate practices—each one as important as the other. Sometimes when I'm making a painting and I need a figural reference, I’ll dip into the sketchbooks and find somebody and make a painted version of that drawing. It’s always a translation, because the drawing is done on the fly with a marker, for example, and when I’m putting it into a painting, it’s in another language.

In my studio, I usually have a bunch of different sized canvases lying around because I know I like to work in different sizes. These days, the paintings range in size from three by five inches to eight feet by five feet-ish, with most being in the middle of that range. Scale is both a bodily experience and a psychological one. With the small ones I feel more comfortable working through an idea or just plunging in and changing things up a lot, because it's smaller and you can change things radically as you go.

The bigger paintings are very pleasurable because I do get into taking my time with something, having it sit there and coming back to it day after day. But I can also certainly get bogged down. So when I'm working on a big painting, I also have other smaller ones going at the same time. It’s almost like a piece of music or something—like an opera versus a really catchy pop song. They're different, but also interesting and challenging in their own ways.

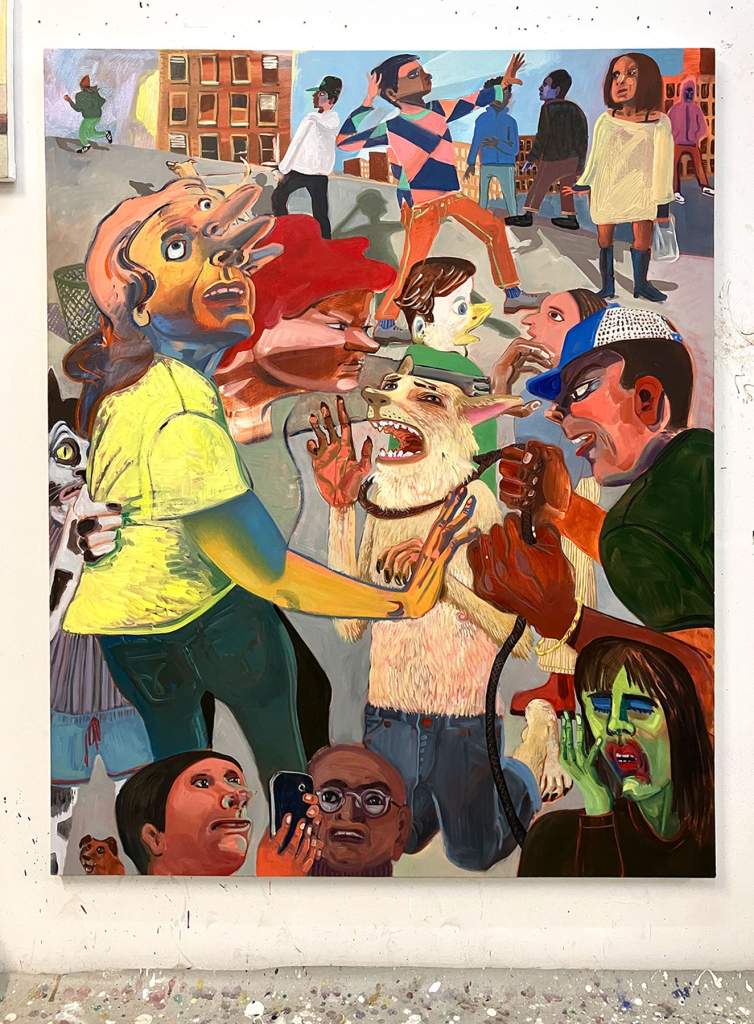

I'm going to have a solo show this fall at a new gallery in New York, the JJ Murphy Gallery. So I’m working on paintings for that. I've been doing a couple of paintings recently with animal-human hybrids. In this painting [gestures to work on studio wall], which I think I'm going to call Dogcatcher, there's a figure who is sort of a semi-dog, semi-human, and there's a man who has a leash around his neck. He’s kind of aggressively moving towards the little dog figure who's kneeling and has its hands thrown up. And then it's a big swirl of activity. There's a couple of figures who seem to be maybe trying to protect that dog-person character. On the far left side, there's a sad or maybe nervous cat human clutching onto one of the people. There's also a duck man in the background. And then there's a whole bunch of disinterested observers who are just doing their own thing and milling around, walking by and looking at their iPhones.

I don't entirely know what I'm getting at there with the combinations of the human animal forms. It’s such a deep metaphoric and mythological thing that human beings have done in stories and images over the centuries. A spelled out interpretation doesn’t matter so much to me. Living in the city things just overlap, come together—affect each other. Humans and animals are so very, very different, yet with domestic animals, we live together with them. It's fascinating to me how we communicate or don't communicate and how there are things we understand—how my dog can let me know that he's hungry or he needs to go outside. He has figured that out. I have taught him, and I have also learned from him. We can basically talk to each other in this way that’s really kind of amazing, if you think about it. We're communicating with another species.

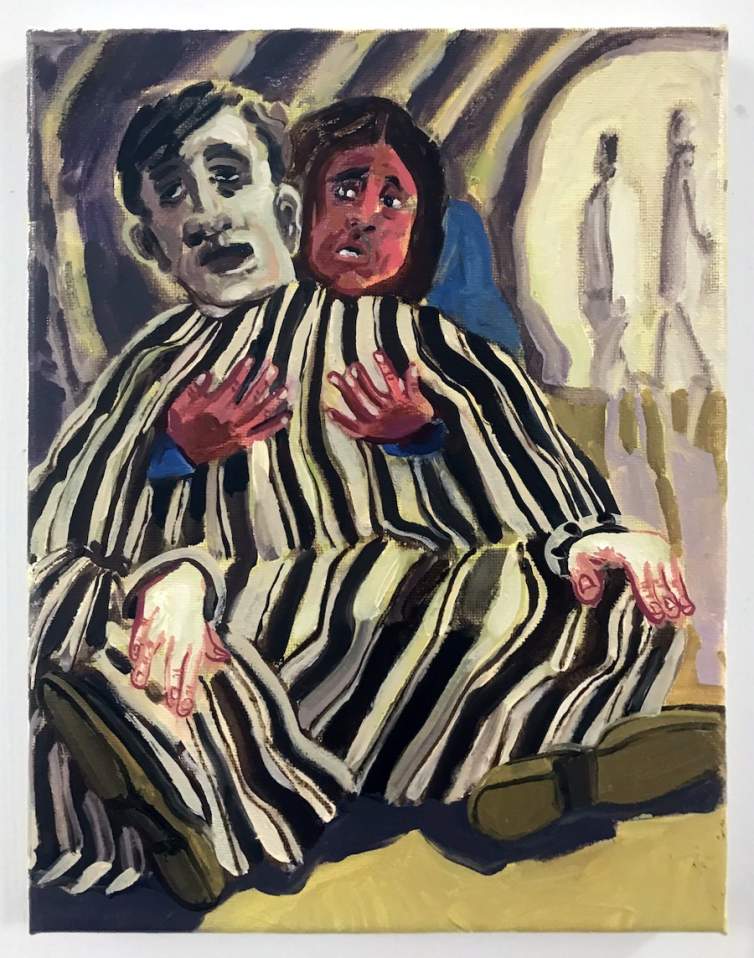

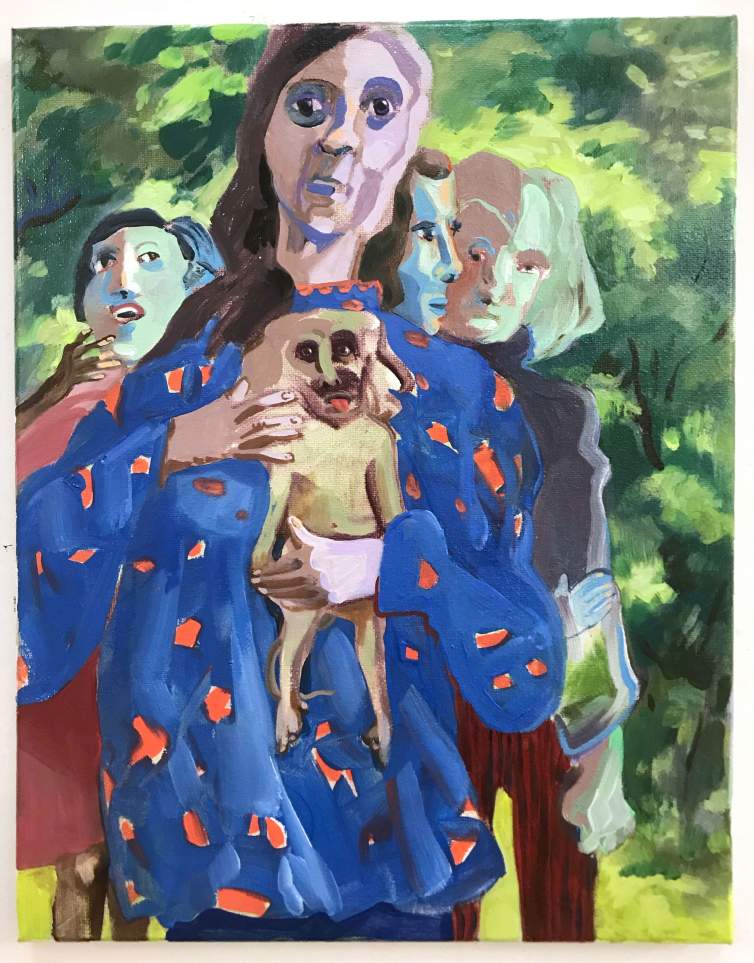

I have another painting called Dog Baby, which has a woman clutching either a very ugly child or maybe a dog wearing a diaper. It's unclear. But she's very protective. And in the background, there are people who seem to be kind of aggressive or judgy or confused.

Often I am trying to explore these uncomfortable zones, where someone just absolutely loves something, but it's also kind of creepy or pathetic or sad. It’s a weird feeling—you sort of feel empathy, like "Oh, this poor woman, she really loves this thing, but oh God, that thing is so weird." It’s kind of like swinging a pendulum between love and horror, or something in between that's also a little bit tender. Again, it probably comes out of deep childhood, or just the feeling of being “other” or being shunned or not fitting in. This is my adult self trying to hit some of those emotions.

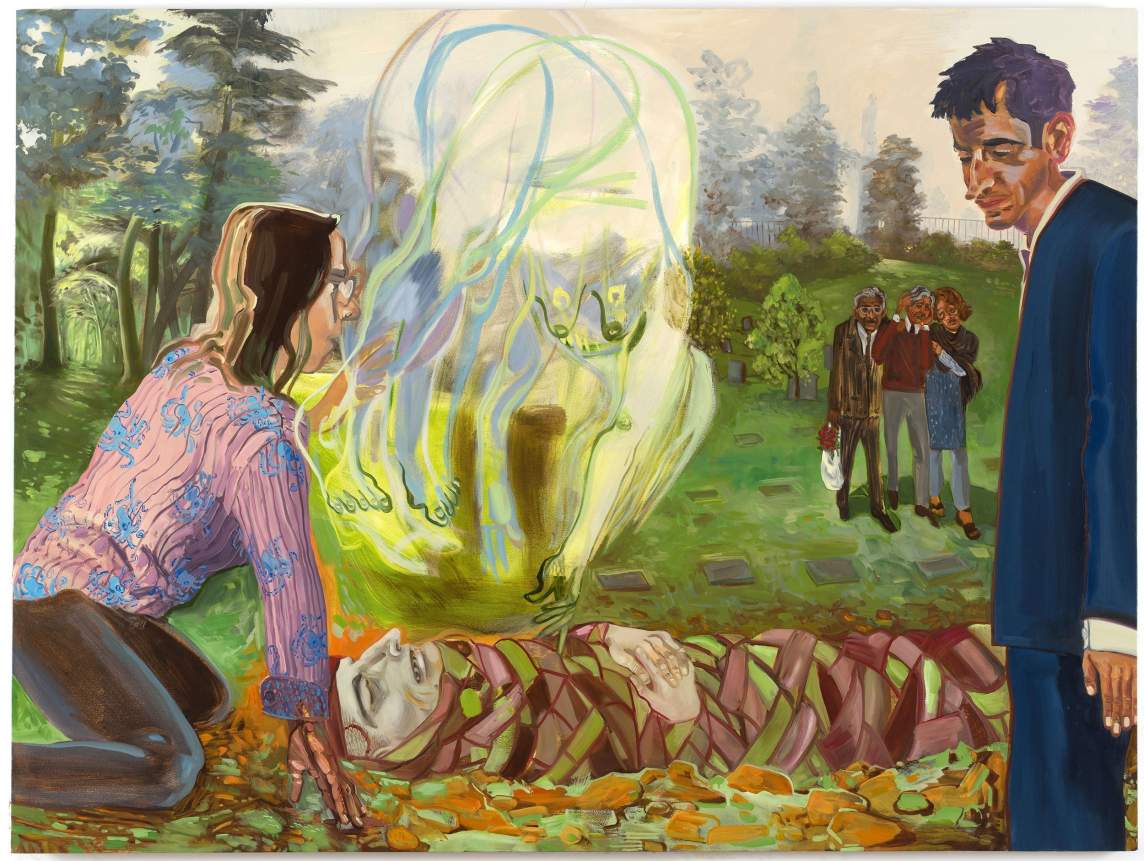

Along with my own studio work, one of the other things that I do is collaborative paintings with Angela Dufresne, who's a brilliant artist, and also my partner of the last five years or so. We've done collaborative drawings for a long time, and also with other people. It was a post dinner party thing that Angie was doing and introduced me to. I really enjoyed that, and then at some point we decided to try and make paintings, not just drawings. We applied to MacDowell together as a collaborative team and got in. Over three weeks, we did 30 paintings together, which was really fun and really hard.

This past summer was the first time we started doing collaborative portraits. So we would have a friend or whoever sit for a portrait, and we would both work on the portrait of them at the same time. It’s really interesting to do that, to work on one painting with another person. We recently had a show of a selection of our collaborative paintings at the galleries at LSU in Baton Rouge. Since very often the people whose portraits we've been painting are fellow artists, we also asked each of them to contribute a work to the show. So it became kind of like a group show, basically. Our collaborations led to other people's work, and in some cases we've inspired other artists to do their own collaborations.

In conjunction with the show, the university had us do a lunch with some undergrads and grads, and Angela had the brilliant idea of doing it as a drawing lunch. So we all had paper and drawing materials, and everybody started a drawing and passed it down. We ended up doing a whole bunch of collaborative drawings, which also went into the show. It was really great. There’s an ever-expanding universe of interesting experimentation that can happen when you open up to having multiple authors of work.

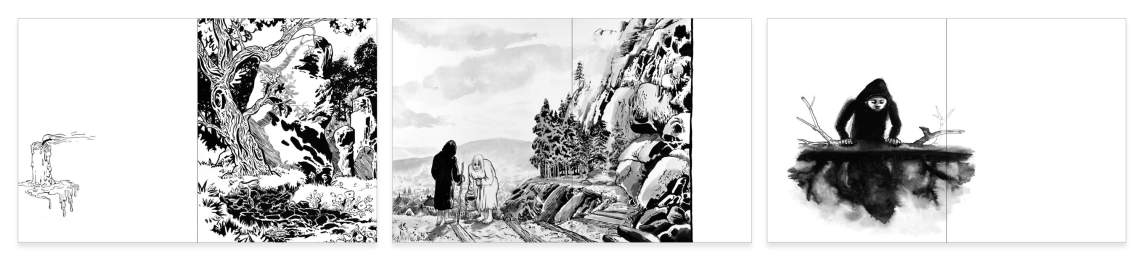

I’m also really interested in making books, and ways to translate my drawings into book projects. I self-published a book of drawings in 2014 that were all black and white gouache drawings, which was what I was primarily making in the studio at that time. I worked with Grace Sullivan, another artist who's also a great graphic designer, to assemble over 100 of these drawings into a book, with no words. She did interesting things like mirrored drawings on opposite pages, or changing the scale of things or deciding when something should bleed from one page to the next.

The book was really generative to make, and sort of echoed my approach with my sketchbooks, which is that I'm allowed to do anything with these drawings. There are some that are imagined, some that are still lifes, a drawing of a photo, some art historical references. You kind of have a through-line, maybe, but can also diverge and link things that you wouldn't ordinarily link in your mind. I've been thinking that I want to do another book, this time in color.

For the solo show that I had a couple of years ago at Soloway in Brooklyn, Grace helped me produce a little edition from one of my small-format sketchbooks. We scanned the entire thing and made a one-to-one version—a printed version of the sketchbook that people could buy at the show. That was a really nice way of showing a sketchbook, and I loved the idea that people could take a copy home and spend time with my sketches in that way. Because even though the sketchbooks are a more private thing, it's also actually a really pleasurable experience to show them to people. I hand a book to another person and that person gets to have a very one-on-one experience. They turn the pages at their own pace, and they have a particular relationship with that, versus walking into a room and seeing a painting.

I feel like if people could actually slow down a bit and really spend some time with my work—or with any art—that would be absolutely wonderful. Deep, slow looking is rarer and rarer these days. I want people to get intrigued, get caught up in trying to figure out what's happening in a painting, in a narrative, in a story. Maybe they produce some relation to what's going on with them in their own lives, or feel some sense of recognition and empathy when they look at my work.

I think this relates to why I like for the narrative in my work to be a bit ambiguous and not clearly spelled out. I feel like that's a much more active way for people to engage with my paintings. That's part of what makes it interesting. My hope is that people look at my work and kind of wonder, "What is the relationship between those two figures?" Or, "What's happening here?" Or, "Why does that man look upset?" A lot of the time I don't know either. For me, it's also an open-ended story.

Interview and editing by Jenny Gill. Learn more about Mala Iqbal’s work at malaiqbal.com and on Instagram.