In the Studio: Samira Abbassy

“My attempt in depicting the human form is almost like a psychic x-ray, so the n...

Shane Darwent is an interdisciplinary artist based in Tulsa, OK, and a 2022 Joan Mitchell Fellow. We interviewed him about his recent work and creative practice in March 2023. The following is an edited transcript of that conversation.

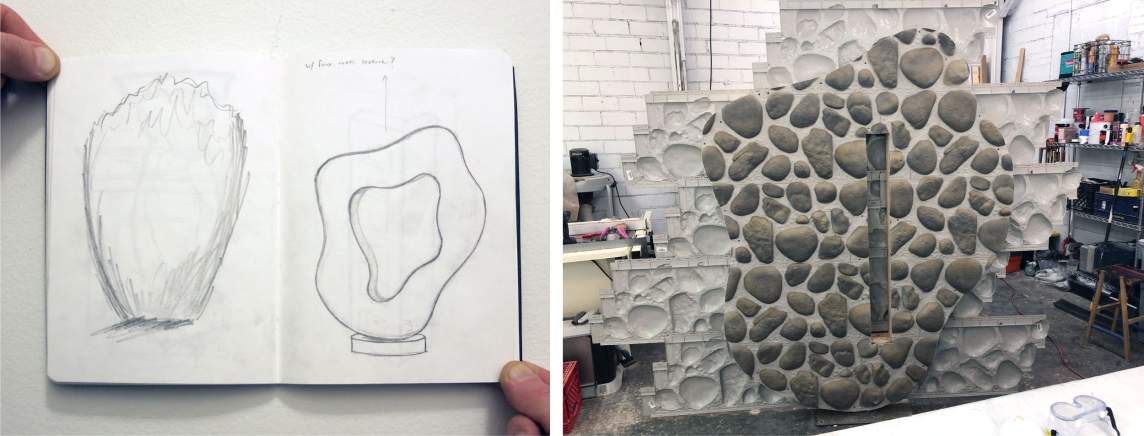

I'm primarily a sculptor and a photographer. Photography has always been the front line of my practice, and I've always made pictures of everyday commercial retail landscapes. I usually have the camera with me when I'm out running the most boring of errands. It’s a tool that helps me make peace with these landscapes that can frustrate me, whether it's navigating a shopping center or a parking lot or other kinds of things in the built infrastructure that can mediate the way you move through the landscape. I started taking pictures of those types of spaces, and then through that, I got interested in making sculptures using the processes and materials that I was photographing.

Those photographs led into sculptures using storefront awning forms and fabrication techniques. I've worked with various building veneers, like vinyl siding and stucco. It's all in service of trying to make peace with these retail landscapes, to sort of understand everything that it presents outwardly, and also everything that it's not—all the cracks and the seams and play in that space.

When I was growing up, art was a tool for me to process the world. My family was very much a "follow your bliss" kind of family, but it was very sports- and popular culture-oriented, so I wasn't really exposed to the canon of important artists. I found myself at art school, where I learned about the icons of modernism and minimalist sculpture, and I started to see how their work existed in these somewhat banal spaces that I was trying to navigate. So my work has been a conversation with those icons of post-war modern sculpture, like Barbara Hepworth or Isamu Noguchi, who were trying to have this communion with the natural landscape.

Now, 50 years after they were working, the natural landscape is so obfuscated and covered up. And so I'm not carving rock, but I'm using rock veneer to have a sort of impossible conversation with where the organic sits within the contemporary landscape. And it's also a tongue-in-cheek conversation with the icons of minimalism—like locating Donald Judd in the parking blocks in the strip mall. So I’m expressing both reverence and irreverence for those forebears, honoring them but also playing with them, and figuring out where they exist in the contemporary landscape today.

With photography being a part of my sculpture practice, there has always been this back and forth, where I'll make pictures that will inspire sculptures and then the sculptures will, in turn, influence how I'm looking at the landscape that I then photograph. But with the awnings specifically, I was initially interested in the surfaces of them and the layers of economic history that were embedded in them.

I went to grad school at the University of Michigan. Not long before, Detroit declared bankruptcy and it was this kind of interesting rebuilding time for the city. I was seeing the layers of the cultural and economic history of Detroit embedded in the fabrics of the awnings. For my first awning sculptures, which I made outside of Detroit, I used discarded awning covers that literally had a history embedded in them.

Now, I've become more and more interested in just the process itself and researching these economies through this very specific building form and technique that's found in these spaces that I'm interested in. It's kind of just taken on a life of its own, like they are awnings masquerading as sculpture, where maybe at the beginning, it was the inverse of that.

Last year, I had a solo show called Sun Smoke at the Spencer Brownstone Gallery in New York, and it was looking at storefront awnings-turned-sculpture, using only black vinyl. Previously, my work sort of tried to bring together everything in the photo works—floor sculptures, awning sculptures—but for that project I really focused on this specific series, which I'm calling Nocturnes. It sort of grew out of the early, dark days of COVID and seeing so many business closures. These black awnings became memorials or overtures for businesses closed or businesses to open again. I've continued that body of work through the last year.

Also last year, I got to do this pretty wild collaboration with Saint Laurent, the fashion house, where I produced 25 site-specific sculptures over the course of the year. They were installed in Saint Laurent’s international flagship locations as well as the Bergdorf Goodman windows in Manhattan. Again, those were the all-black storefront awning pieces that, for me, were starting to speak less specifically about any particular retail space. I was stepping back a little bit and considering these bigger questions of light and dark, weight and weightlessness—using these commercial processes to have bigger, metaphorical conversations.

Now, that has led directly into a solo show that I'm working on right now for Texas A&M University’s School of Art and Architecture. Most of the pieces for this Texas A&M show have no graphic imagery on the awnings. The vinyl, even if it's repurposed, looks completely new. So I'm really letting the material language of that building process take center stage, and using my studio as a place where the material can be something more than just an object in service of this one narrative or this one business.

There's one work in particular that's kind of become the anchor for that show for me, which is a long, black awning wall frieze. It's kind of a quintessential form called a shed-style storefront awning and the pitch of it alternates as it moves across the wall for a 15-foot span. All of the elements of this piece are wrapped in the same black vinyl, but because of the slight pitch that each one has, the black becomes a completely different color as it moves across the wall. As you move around it, it changes from what looks like just a black monolithic bar to something that reveals itself as your body moves. And then, there are these slivers of light that are created through the pitch of the awnings changing, and the light just becomes impossibly white and bright, leaking out from that black vinyl.

In the show, new awning works are paired with photographs installed directly onto the gallery walls. I’m going to be an artist-in-residence on campus for several days leading up to the show and will be taking photographs of the nearby shopping centers. I want there to be a call and response between the representations of built space from the photos and the physical space activated through the sculptures and dimensional works. There is also usually an interesting, gritty texture evident in the pictures, like crumbling cement or cigarette butts, that I think pairs well with the newness of the awning vinyl or freshly painted objects.

If there's a through-line in what I've been scratching at for a number of years, it's the exposing of the veneers that shape our surroundings, but also a communion with that. I've never wanted the work to be like wagging a finger and saying, "Look at the hollow shell of our built environment!" I'm really interested in the hidden labor that exists in these spaces, and I've developed really amazing relationships with fabrication communities and with the storefront awning shop here in Tulsa called Awnings of Tulsa. We've had this ongoing series of projects that we've worked on, and it's illuminated an architectural process into this sort of layered art form. And for the fabricators, it's also been a chance to recognize the work that they do as inherently crafted and beautiful and art-like.

When I think of people encountering my work, if they experience any of that transcendence of a material, I think that that's all I could ever hope for. Like, "Hey, this exists narrowly in my navigation of the world as this one thing, but it's also this other thing that represents a whole other unseen community that shapes the landscape that we live in."

In addition to the Texas A & M exhibition, I have a show coming up in the summer at Tinney Contemporary in Nashville. I also have a project coming up in Frankfurt, Germany, next spring, which actually grew out of the Joan Mitchell Fellowship, as that’s how the gallerist found my work.

Another cool thing that I’m developing right now, that’s tangentially related to my studio practice, is a regional micro-residency exchange called Plains Exchange. I'm not from the Midwest or the Southern Plains—or whatever Tulsa is—but I’ve been here for the past few years in the Tulsa Artist Fellowship. It’s a small arts community here, and there are a number of other growing arts scenes in the region, like Oklahoma City, Kansas City, Dallas, and everything that's happening in Northwest Arkansas with Crystal Bridges and all of the Walmart money. It's a pilot program now, but in this first iteration, it's a one-to-one exchange. We're sending a Tulsa-based artist to Northwest Arkansas and putting them up for a two-week residency and connecting them with the local art scene there. And then, we're bringing an artist from Northwest Arkansas to Tulsa for a two-week period. I'll get to be their liaison and facilitate studio visits and an open studio and a conversation with them while they're here.

Plains Exchange is branching out from that. I have plans to bring folks from Kansas City and Dallas to Tulsa, to try to grow the conversation in a holistic way between these different arts communities. None of these towns will ever be New York or LA, and so if we could pool our resources a bit and help connect artists in these neighboring cities with the resources that each other have access to, then it seems like we could maybe be bigger than the sum of our parts and build something with more connectivity. I'm not a social practice artist, but I like connecting communities, so it's something I'm excited about.

Interview and editing by Jenny Gill. Learn more about Shane Darwent’s work here.